Overengineering the Problem

A story about dreaming too big too fast, over-engineering a problem that didn’t exist yet, and learning to pivot when reality forces a change of plans.

You might’ve heard of over-engineering the solution before… but have you ever heard of over-engineering the problem? Well, that’s what I did today.

How, you might ask?

Well, it all starts in this research project/class I'm in (it's a pretty confusing mix, but I mean I guess it counts for my degree?) where we're developing a digital twin of almost the whole universe. Now you might go: "...wait, Sean, that sounds pretty neat!" — and be looking forward to this post being about the intricacies of the codebase (which, to note, has around 16k commits... and if you don't know GitHub terms, it's a lot of moving parts and updated code), which I will admit there are quite an interesting number of.

Starting off the story from last semester, the project I was working on was making the whole program — with a physics renderer and complex logic — possible to be played in multiplayer. From scratch. With practically no direction for the project and no support from my team lead, I developed a pretty solid high-throughput TCP server and client model which would hopefully serve as the foundation of multi-user state synchronization.

For specs: it sustained 440,889 req/s with a 32-thread pool and a line-delimited protocol, benchmarked by a C++ load generator spawning 64 threads × 500 requests per connection to verify scalability across worker threads.

Now: "to what end are you going about lengths on this subject about?" one might ask.

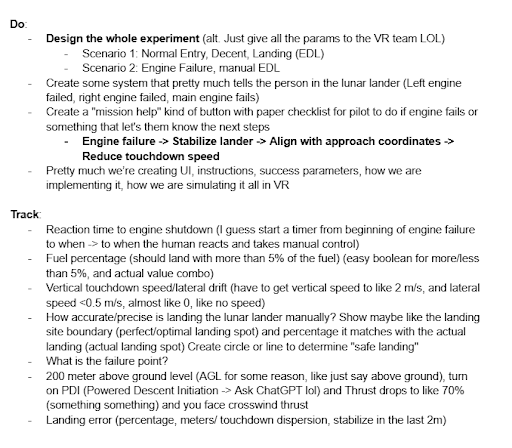

Well, last semester's tone really set the scene for the stage of this semester's work, where our subteam of the Artificial Gravity Space Station subteam (yes, you heard that right — double subteam inception) was told to work on running a sim of a lunar lander being in its last ~200 meters of landing.

|

|---|

| Figure 1. Design Criteria/Plan for the semester |

Presenting it in our biweekly standup, I pitched the idea for it to CONNOR JAKUBIK (the lead developer of our project) with something like:

"Imagine you have this person called CONNOR letting the lunar lander use its GNC system to automatically start going into EDL — Entry, Descent, and Landing — which is the critical phase of a space mission to get a spacecraft from the top of an atmosphere to the surface of a celestial body. However… oh no! One of the thrusters has malfunctioned and now you have to take manual control. What do you do? That's what the goal of this sim is trying to figure out — how fast a person reacts and how accurately they can control the final descent in case of an emergency."

Now yes, that was quite long, but just imagine the storytelling and interest I was garnering in our project… because I joined this team for my interest in this project and the possibility of getting to use our Eight360 NOVA (which is a whopping $150,000 piece of equipment per year for leasing) for research in Mixed Reality and Human–Computer Interactions, and I wanted to share it with everyone else too.

Well, let's say the idea was commended quite a bit... but the Lunar Lander Unreal assets and the base sim we were supposed to be implementing it into weren't even ready yet. So this complex and beautiful plan — this intricate problem we were tackling — was really all lost in seconds to matters beyond our subteam's control.

Luckily, the story doesn't end there.

So we over-engineered the problem — taking an over-idealistic assessment of our current resources and having to start back at step 0 (making the initial sim). Now what?

Well, our decision was to pivot from our initial plan with the lunar lander and implement the same test scenario and tracked metrics in the already-working Orion docking sim, which already had built-in movement (but for some reason with IJKL instead of WASD). And we're working on implementing our tracking UI, thruster malfunctions, and everything else into it.

|

|---|

| Figure 2. Current Orion Sim |

What I've learned from these experiences are:

- Sometimes things really do just get thrown at you, and if life gives you a rendering engine for a digital space twin, make a TCP server out of it (if you can't do anything, at least learn from the experience).

- Make sure you validate your ideas before moving forward. Even though our initial problem got shut down, it's a lot better that we had to pivot at an earlier stage instead of trying to force our initial solution — which would have led to a pretty spectacular fail.

- Don't get caught up in the nitty-gritty details when you first start doing something hard. Get a good perspective on your problem and learn to love it, or else it's hard to enjoy really working on it.